|

Welcome |

About Us |

About Padre Martinez |

Virtual Library |

Virtual Museum |

El Crepusculo de la Libertad |

Links |

Will and Testament

Administration of The Presbyter Don Antonio José Martínez

COMMENTS ABOUT THE LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT OF THE

PRESBYTER DON ANTONIO JOSE MARTINEZ

By Vicente M. Martínez

Introduction

Much has been written about the life and legacy of Padre Martínez, Cura de Taos, and his achievements as a visionary and leader in the fields of religion, politics, and education - religious and secular. Not much has been written about his personal life after he was excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church by Archbishop Jean Baptiste Lamy in 1858. A thorough examination of the personal estate of Padre Martínez, who died on July 25, 1867, provides insight into secular and post-excommunication religious aspects of his life and will shed more light on his activities during his final years. Foremost in this document is that he never lost his faith in God or the basic tenets of his Catholic religion as evidenced by his own testament, the construction of his oratory, the graveyard and chapel with the detailed description of its contents. It was through these particular holdings that he continued his priesthood and remained faithful to his followers in his beloved community - Don Fernando de Taos. Like his father, Don Severino Martínez, before him and his brother’s Santiago and Pascual Martínez, he engaged in economic endeavors that included large holdings of farmland, a flourmill, and livestock loaned in the partido system. He also had a mistress, putative children, and a slave, all of whom are named and provided for in his will. Finally, he died at peace with his God, himself, his family, and his fellow vecinos of Don Fernando de Taos. His estate was valued at close to $10,000, an impressive sum for that period of time.

Regarding the language of the will

The Spanish used at the time of the writing of this will, as well as the calligraphy of the recorder, certainly posed many problems in trying to convey meaning. The document used was an 1867 copy of the original will, and each recorder of that time had a unique and particular style of writing. Obsolete spelling, punctuation use, vocabularies (including religious, local, and Indian-derived words) and verb tenses, as well as a Baroque-like word order in terms of syntax, all presented challenging translation problems. I purposely avoided a completely modern translation in order to maintain some of the flavor and elegance of the original document, even if the reader has to ponder the meaning. There can be no doubt that the translation of a document such as a will certainly brings one much closer to the author, and it is my hope that the translation I present here is accurate and faithful.

The Spanish transcription of the will and inventory is faithful to the recorded copy of the Spanish document, word for word, as it was written and keeping the same punctuation, capitalization, and spelling. I believe that unnecessary capitalization was used to place emphasis, or importance on certain words. The copy lacked proper accents, and the letter “s” was substituted for words normally ending in the Castilian “z.” In the original document the tilde (~) was represented by a straight line (–).

A note about the documents

These documents, presented in English and Spanish, consists of three sections: Part One: The Sworn Declaration of the Administrator, Part Two: The Last Will and Testament, Part Three: The Inventory, and Appendix A: Glossary of Ecclesiastical Terminology. Padre Martínez began writing his will in June of 1865, describing all of his holdings, and by his own testament he finished it in the last days of his life as he lay ill and in bed. He may have dictated his final bequests to someone trusted, perhaps either Santiago Valdez or Pedro Sánchez, both related to and educated by him and whom he named as executors. The reader is reminded that Padre Martínez, because of his understanding of American land-use laws, taught his law school students the proper and legal way to draw up wills and testaments.

Acknowledgements

I am most

grateful to my friends and colleagues Virginia Snyder of Delray Beach, Florida

who edited the first drafts of this introduction, Elena Nápoles

Goldfeder, Ph.D. (Retired Professor of Spanish Literature) of Hypoluxo Island,

Florida, and Padre Juan Romero, also retired, of Palm Springs, California who

advised and assisted me with the initial translation. I am further grateful to

the Rev. Thomas Steele with whom I collaborated on the final translation. Under

his editorial skills the University of New Mexico Press, in the near future,

will publish this document, along with the 1838 autobiography of Padre Martínez

also known as the Statement of Merits of the Presbyter Antonio José Martínez and the 1877 Biography of Padre Antonio

José Martínez - Cura de Taos by Santiago

Valdez.

I am

grateful to Dr. Estevan Rael-Gávez and the staff of the New Mexico State

Records Center and Archives who assisted me in locating the documents, and who

recopied illegible documents, and assisted me in some cases with the spelling

of some of the inventory items. I

also wish to express my gratitude to the following: Sylvia Rodríguez, David

Weber, Tómas Atencio, E. A. Mares, Ward Allen Minge, Corina Santistevan, Jerry

Padilla, Robert and Ben Montoya, Juan Chavez, Alberto Vidaurre, Edmundo and Ben

Vásquez. Finally, I am most

grateful to my late parents, Arturo and Teodora Martínez y Salazar, who

instilled in me a love for history, family and culture, and to my son, Antonio,

who encouraged me to immerse myself in historical research.

Part One: Sworn Declaration of the Administrator

Santiago Valdez, whom Padre Martínez recognized as “of his family,” and Pedro Sánchez were named the executors of the will. However, Pedro Sánchez was married to a favorite niece of Padre Martínez and was also the Probate Judge, so Santiago Valdez became the sole administrator and executor of the will. Contained in these documents of the will is the Sworn Statement of the Executor, Santiago Valdez, whereby he presents himself to the Probate Court to be appointed Administrator of the will. The surety bond was required by the Probate Court to guarantee the executor’s faithful performance of duties and an equitable accounting of property received and distributed; however, this particular document does not identify the actual surety amount. Surety may have been waived due to the familial bond between Valdez and Sánchez. Finally, Santiago Valdez, through the letters of credentials, was legally named administrator of the estate of Padre Martínez.

Part Two: The Last Will and Testament (with some comparisons to the Inventory)

Ritual

First and foremost, Padre Martínez identifies himself as a vecino, which literally means “neighbor.” However, in the latter part of nineteenth century New Mexico the term vecino had both civic and cultural connotations. In a break with early caste classifications, the term vecino was initially allocated to upper classes of “Spanish” ancestry, but after 1850 it became a status that could be achieved through raising one’s status in life, i.e coming up through the rank and file, and through marriage or kinship. In all cases though, it was used as a term to distinguish one from being Indian. [1]

Firstly, Padre Martínez requests that he be buried in his oratory dedicated to the Immaculate Conception, to whom he was devoted under the Spanish name of La Purísima Concepción. [2] According to his correspondence of October 1, 1856 Padre Martínez advised Bishop Lamy that he had built a private oratory and walled cemetery on his property and at his own expense. The construction was undertaken after the Bishop had appointed Padre Don Dámaso Taladrid to replace Padre Martínez as pastor of Taos in May of the same year. [3] According to Martínez, the oratory was built because Taladrid had made it difficult for Martínez to say mass in the parish church and because he (Taladrid) had been making derogatory comments against Martínez. [4] As early as June 1856, Taladrid had reported to Bishop Lamy that Martínez had built a private oratory.

Padre Martínez would not have been

buried in the Catholic cemetery because of his excommunication.

Oratory and/or Chapel

In his written description of the

structures, Padre Martínez uses the terms capilla and oratorio. “I have a Chapel and

graveyard…adjoining said Oratory built on my own land.” (p. 1). The Inventory,

which utilizes the term oratorio,

lists two Oratories and two graveyards and provides dimensions of the land,

apart from the buildings, measuring 33 3/4 varas long by 21 1/4 varas wide (93.74’ x 59.02’). The dimensions indicate a plot of land of about a twelfth of

an acre that seems sufficiently adequate to contain two small buildings and a

graveyard. In historic New Mexico,

the terms capilla and oratorio appear to have been interchangeable. It is also known that some cemeteries

had an oratorio used to place

bodies in repose for gravesite services before burial. However, according to

Fr. Tom Steele, S.J., the term “oratory”… according to the canon law of that

period, was very much focused on saying mass.”

[5]

The will does not give a precise

location for the chapel and oratory other than to list it as an eastern

boundary to a tract of land that he sold behind his residence. ” I sold a tract, part to Antonio

Manzanares and another part to Aniceto Valdez. [This tract] is bounded on the East by the fence of

the Plaza, my Chapel, and the walls of the Sisters property”(p. 2). Per the

will, the Padre’s oratorio appears to be

a separate building located to the west of the chapel but on the same plot of

land, and it was described in the inventory and somewhere towards the back of

his residence. Extant

correspondence between Taladrid and Lamy in 1856 places the location of the

oratory in, or near the residence of Padre Martínez. Pedro Sánchez in Chapter XI of his book

[6]

states: “…Allí en sus propios terrenos, edificó á su propia costa una

grande y hermosa capilla en la cual ejerció su alto ministerio” (there, on his own land and with his own funds he built a large and

beautiful chapel where he practiced his lofty ministry). Also, Dora Ortiz

Váquez, in her book Enchanted Temples of Taos describes the

reburial of Padre Martínez as originating from the oratory where he was buried

and taken in procession to the Taos Association Cemetery.

[7]

And finally, an 1891 article on the

same topic of the reburial states that the procession began at the home of the

late Santiago Valdez, formerly the home of the deceased priest, where he was

buried.

[8]

Therefore, based on the Padre’s own

words and these historic descriptions it can be concluded that the oratory,

chapel, and graveyard were either a part of, or adjoining his residence. In his

will Padre Martínez appointed Santiago Valdez and Vicente Romero as the mayordomos of the chapel. More research will be required to determine the exact location of this

and other properties listed.

In

his statement about his chapel and its contents Padre Martínez gives a thorough

description of its contents and furnishings, and he meticulously describes each

vestment, article of linen, and other furnishings, religious figures, and

utensils used in the celebration of the mass, and to support his ministry. Appendix A, at the end of the

Inventory, contains a partial Glossary of Ecclesiastical Terminology relative

to the vestments, linens, and early religious objects mentioned in the will.

The contents described by Padre Martínez are consistent with the objects

described in the Inventory, prepared by the estate administrator Santiago

Valdez. In effect, Padre Martínez

recreated his own church, which was listed in the 1860 census as having 500

communicants. According to Father

Steele, “the pastor from Taos from 1858-76, Fr. Gabriel Ussel, said that about

a third stayed with Padre Martínez.”

[9]

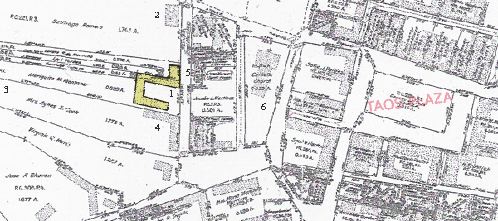

Figure 1 1915 JOY SURVEY: Plat showing Private Claims within the

Taos Pueblo Grant – Taos

Town site: US Bureau of Land Management.

1915 Configuration

of the Plaza de Don Fernando de Taos

By

1915, Figure 1 above, what remained of the Padre Martínez residence (1) was a

“U” shaped configuration with an extension on the northeast corner that may

have been the María Soledad Romero residence, and immediately to the north, the

Santiago Romero Home (2). The Padre Martínez house and property was bounded on

the east by (5) -a public street; on the west by (3) the Manzanares Arroyo; on

the north by a stretch of wall -not shown; and although no southern boundary is

given, it may have been the space between buildings 1 and 4, and later

described in the will as a passage way to the house of María Teodora Romero

(4). Our Lady of Guadalupe Church

is (6). The Sisters convent and school would have been across the street and

approximately 125 five yards north of the Santiago Romero home (2).

Given this configuration, the

current locations are (1) Padre Martínez Home and Las Casitas West

Condominiums, (2) Santiago Romero Home (Don Fernando and Padre Martínez Lane),

(3) Manzanares Street, (4) Guadalupe Apartments, (5) Padre Martínez Lane, (6)

Guadalupe Parking Lot. The chapel

and oratory may have been adjoined to the Padre Martínez residence (1) on the

southwest side and directly behind the Guadalupe Apartments (4). During the construction of the Yaxche

Learning Center in 1999, human remains were found directly behind the Guadalupe

Apartments and the state Office of the Medical Investigator was notified. However, no excavation of the site was

made to determine the reason for the placement of the remains.

Residence and Other Holdings

Padre

Martínez describes his residence as follows: “in the plaza of Don Fernando de

Taos, where I presently reside is in a small patio surrounded by porches on the

inside. The stretch of wall on the north side belongs to the house of María

Soledad [Romero], a member of my family, which I deeded to her with a yard and

back-corrals. Beyond the porches

that belong to me is my own square with its back-corral buildings” (p.2). María Soledad was one of his

illegitimate daughters.

In

describing a tract of land behind his residence, Padre Martínez gives the

following boundaries: …” I own a tract of land that is bounded on the South by

the house of Juan Valdez, the upper part [of the tract] has a direct line

heading towards the West where it meanders across the [Manzanares] arroyo… On

the North it is bounded by said arroyo that runs behind the old plaza and with

land that I granted to Santiago Valdez, a member of my family.“ (p.2) It is interesting to note the reference

to the “old Plaza,” which given the boundaries above, would have been

west-north-west of the current plaza. In the Inventory, this land is described

as “22 varas of land behind the Sisters convent, chapel, and cemeteries, and my

residential house to the [Manzanares] arroyo on the west.” (p. 2) The arroyo, if one follows the

historical configuration of the terrain, would have begun near the current

intersection of Camino de la Placita and Valverde Road and meander west and

then south. It was a natural

boundary between La Loma and Taos proper. The identification of this property and the true location of his chapel

will require more research of property titles of the land surrounding the

Plaza.

It is clear from the will that

Padre Martínez had large holdings of land throughout Don Fernando de Taos and

beyond and a modest number of livestock, mostly cattle and goats. In those days, the standard measurement

of land was the vara, which by current US measurement standards would be equal to 33.3

inches, or one pace.

[10]

I have chosen to retain the Spanish

term as it recurs in the will.

Other lands listed in the will

include approximately 400 varas of land

in San Cristóbal, a house and land in Arroyo Hondo, and the same in Arroyo

Seco. These lands also appear in

the Severino Martínez will and they were most likely given to Padre Martínez by

his mother. It should be mentioned

that Don Severino Martínez was an original petitioner for the San Cristóbal

Land Grant. The houses and land

described in Arroyo Hondo and Arroyo Seco do not appear in the Inventory, but

the Inventory does list a four-room house and 100 varas of land in Desmontes and another 108 varas of land adjoining this property. Des Montes is located mid-way between

the two communities. The two San

Francisco del Rancho (Ranchos de Taos) gardens and the 63 vara Coca farmland are consistent in the Inventory of the

will. The Inventory identifies

another 63 varas adjoining the

Coca farmland,

[11]

and 50 varas of farmland on the ranch of Martín Maes, no location

given. Again, an extensive title

search would be necessary to determine the exact location of these holdings.

Padre Martínez states in the

will “I am owed various amounts of

money for obligations that are recorded in account-books and ledgers and labor

credits from workers who have not finished payment. All of this shall be accounted by my executors when they

prepare a detailed, item by item, inventory after all of the [outstanding]

payments have been made” (p.4). On the last page of the inventory, and under the title of Observation,

Santiago Valdez attests that “the debts incurred to the Estate do not appear

here because they have been recorded in cashbooks and it will be necessary that

the debtor be present for [debt] liquidation in order to clear all debts”

(p.1). A search continues for a probate document that show the disposition of

the items contained in the Inventory.

The Estiércoles Land Issue

On April 26, 1847, Padre Martínez

purchased a tract of land in Estiércoles (El Prado, NM) from Taos Pueblo tribal

leaders for a sum of $532.05. Taos Pueblo Alcalde, Rafael Espinosa, Pablo

Martínez, Pauline (sic) Suazo, Pablo Zámora and Santiago Martínez, Chiefs of

the Pueblo of Taos, each respectively signed the deed with an “X.” The

boundaries and size of the tract are as follows. "The land

which consists from the place called Estiércoles and lands of Pablo Gallegos on

the south, to the north by three alamos the

trunks of which shall be a monument; on the east by the Lucero River, and on

the west Arroyo Seco Route and Rio del Norte, further the west part as many varas as comes up as far as the three alamos one thousand four hundred and eighty-two varas was the width of the measured land."

[12]

The transaction took place over two

days, the first to convey the deed and the second day to clarify that the

number of varas pertained, specifically,

to the width of the tract. The

signatories were present both days.

In the ensuing years following the

conveyance of the land by deed there had been much dispute from Pueblo tribal

leaders about the legality of this transaction, as well as others that occurred

in the Taos and the upper Rio Grande area. The first settlement of Don Fernando

de Taos in the later part of the eighteenth-century occurred within the Taos

Pueblo four-league square grant made by Spain during the Spanish Colonial

period. The proximity of the Taos

settlement was beneficial to both Pueblo and Spanish settlers because it

allowed for mutual defense from hostile Indian raids. Under Mexican law, it was permissible for citizens to sell

land from Spanish grants, and these rights were conveyed and retained under the

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the US – Mexican War in 1848. The Treaty recognized the Pueblo

Indians as Mexican citizens, except for voting, and in doing so conveyed

federal US citizenship upon them. Such status prevented the Pueblo Indians from enjoying US federal

protection guaranteed to other Indian tribes under the Trade and Intercourse

Act of 1834. Throughout the later part of the nineteenth century the issue was

debated in the highest courts of the land and, in 1913 the United States

Supreme Court decreed that Pueblo Indians necessitated federal protection

offered by Indian status.

[13]

The issue was finally settled in 1924

with the enactment of The Pueblo Land Act by Congress, which established the

Pueblo Land Board that settled 50,000 acres of non-Indian claims, including

those from the Town of Taos. The

Joy Survey of 1915, presented in Figure 1, identified the exceptions within the

town. The Act also established

that Pueblo lands could not be acquired without Federal approval.

Taos Pueblo oral history and

testimony presented to a congressional committee contends that Padre Martínez

betrayed Pueblo elders because the land, seen as a gift, was allegedly an

exchange for intervention on behalf of tribal leaders that were hanged for

their role during the insurrection of 1847.

[14]

The deed was dated four days before nine men were hanged on April 30, 1847, and

according to Pueblo oral history, the intervention never took place. Research of the historical record shows

that Padre Martínez did intervene on behalf of all of the condemned; however,

the will also indicates that others who received a portion of land for their

assistance may have either been parties to the purchase or served to transact

the acquisition of this land on the Padre’s behalf.

[15]

I am currently preparing another paper

that examines the events of the 1847 Insurrection, the transaction, and the

role of Padre Martínez and disputes the claims made.

[16]

The first

conveyance of Estiércoles land after acquisition from the Pueblo occurred on

May 4, 1848, when Padre Martínez gave 200 varas of land to the Presbyter Eulogio Valdez and others.

[17]

Again, fourteen years before his death,

on Feb. 28, 1853, Padre Martínez conveyed a house and land in Estiércoles to

his adopted son Santiago Valdez, “which began at the Indian land boundary and

continued further down, from said point this last bequest continued to the Rio

Lucero, and another 100 varas from that

point to the final portion of land belonging to Vicente Romero west of the

Estiércoles ditch”(p. 5) Santiago Valdez

assumed his share of Estíercoles per the will through probate on Nov. 5, 1867. The will indicates earlier gifts of

land in 1853 to his daughter María de la Luz Romero and son George, and their

mother Doña María Teodora Romero. Clearly, the Estiércoles land was used as a homestead for his children

in the community of El Prado, just three miles north of Taos. The Estiércoles property also

lists a “mill in operation,” indicative of an economic resource along with

farmland already mentioned, and animals held in the Partido system.

Livestock in Partido

Livestock was contracted out to

various people through the Spanish partido system that was very common in the sheep industry in

the latter half of the Nineteenth Century in New Mexico. The partido (contract) was

similar to other indenture systems such as sharecropping, and whereby the partidario (contracted) received a flock of sheep (in this case cows or

goats), or partida (share) from the patrón (contractor). The contract required that a return of a certain percentage of each

year’s increment, usually 20%, which was due at the end of the contract

period. The Patrón was obligated to provide

protection from hostile Indians, access to grazing lands, and loans for food

and provisions. Like the

sharecropper, the partidario was subject to predators, the elements, raids and rustlers,

and he rarely succeeded in achieving his own flocks or herds.

[18]

These Spanish terms have also been

retained in the English translation.

In the will Padre Martínez indicates that he is owed

ninety-four breeding cows and five bulls under partido; however, the inventory lists sixty-six cows and six

bulls. In the will he does not remember the number of goats under partido, but the inventory lists 110. Under the title of “Hoofed Animals” are

goats, donkeys, oxen, and cattle, all potential sources of labor and

subsistence. During his lifetime,

Padre Martínez was known for his generosity, and during times of need he gave

grain and livestock to the poor.

Progeny of Padre

Martínez

Progeny

is a controversial issue with respect to Padre Martínez because of the moral

issues it raises with regard to the priesthood and vows of celibacy. Within the historical context, in my

opinion, this issue was insignificant when compared to the magnitude of his

accomplishments, and it must be pointed out, his moral conduct was not listed

as a written factor in his excommunication. Very few documents, other than the

birth records have been located that discuss progeny. Fr. Dámaso Taladrid, who

replaced Padre Martínez after his suspension in 1856 did look into the issue of

progeny for Bishop Lamy but did not turn up anything conclusive. An 1863 report by Episcopalian Bishop

Josiah Talbot was more conclusive stating, “Padre Martínez, a far as we can

learn, still lives with his Mexican mistress – his children being known

as nephews and nieces in his family.”

[19]

My

initial source for information about the progeny came from the book, But

Time and Chance by Fray Angélico Chávez who

identified the progeny from Doña María Teodora Romero, the Padre’s neighbor and

housekeeper.

[20]

Unfortunately, Chávez was incorrect in his identification of Santiago Valdez

whom Padre Martínez referred to as “mi familiar (of my family)” in his will. A thorough study of the information presented by Chávez was undertaken

by me in 2007 and was presented in two papers published in the New Mexico

Genealogist Journal,

[21]

which can be found elsewhere on this web site. The baptismal information

presented below is taken from primary sources, i.e. scanned copies of baptismal

records from the Archives of the Archdiocese of Santa Fé many of which were

provided by the New Mexico Genealogical Society, and other source as annotated.

[22]

It

is only through the will that we understand the love shown for his progeny

through gifts and bequests of goods and property before and upon his

death. He conveyed property to

individuals identified by name without specifying their relationship to him,

except for his brothers and sisters. An exception was Santiago Valdez whom he

declares that he adopted and raised. He was most generous to Valdez and to María Teodora Romero as evidenced

by the properties that he gave to both throughout his life and as bequeathed in

his will.

His Marriage and First

Child

The Last Will and Testament of

Padre Martínez contains a brief statement acknowledging his legitimate wife and

daughter as follows: “I declare that in 1812 I was married and veiled

in first nuptials with María de la Luz Martínez, and by this union we had a

daughter who died in 1824. I have

nothing more to say about this.

[23]

”

On May 20, 1812, at the age of 19, Antonio José

married María de la Luz Martín, the daughter of Manuel Martín

[24]

and María Manuela Quintana of the Plaza de los Martínez in Abiquiú. More than a year later María de la Luz

gave birth to a daughter also named María de la Luz. My great-grandfather Santiago Valdez, in his 1877 biography

of Padre Martínez, stated that the mother died in childbirth and the daughter,

María de la Luz, died twelve years later in 1825. The cause of her death is

unknown, and according to Fray Angelico Chávez no death records exist in either

Taos or Abiquiú. A few years after

the death of his wife Antonio José Martínez entered the seminary in Durango in

1817 at the age of 24.

Santiago Valdez: Obedient Son, Controversial Paternity

Santiago de JesúsValdez

[25]

was born on July 19, 1830 and his baptismal record reads as follows: On July 22, 1830, I, Don Antonio

José Martínez, anointed a three-day-old creature of Don Fernando with Holy Oil

[of Catechumens] and with Sacred Chrism. Don Santiago Martínez had already baptized him because of emergency with

water, saying in Spanish the proper words of the required [Trinitarian]

formula. He gave the name of this

infant as Santiago de Jesús, illegitimate son of María Estefana Madril and

father unknown. Maternal Grandparents: Bernardo Madril

[26]

and Maria Ysabel Lopes, both dead. Sponsors, "el referido

bautisante” (the referred baptizer - Don

Santiago Martínez) and (his wife) María de la Luz Lucero, all neighbors from

the barrio of Don Fernando.

[27]

After his birth, Santiago was

placed with the family of (José) Ygnacio de Jesús Valdes and his wife; María

Dolores Duran of Taos, and Santiago took the surname Valdez.

[28]

This arrangement would have been made by a mutual agreement between Padre

Martínez, María Estefana Madril, and Valdes.

My family oral history has always

maintained that Padre Martínez was the real father of Santiago de Jesus Valdez

but no written record remains. Citing the baptism of George Romero (presented in the next section), Chávez

maintained that Padre Martínez would not have performed the baptism of a

natural son because it is “forbidden by canon law and proscribed by much more

ancient Church custom, even in the case of legitimate parents, but it had taken

on an aura of superstition which was more compelling than church laws and

dogmas. Hence, he got his brother Santiago to pour baptismal waters on

George Antonio (Romero) beforehand.”

[29]

(Emphasis mine). Following this logic, the baptismal record of Santiago de

Jesús Madril, cited above, makes a compelling argument for the same

possibility.

Santiago married María Agustina

Valdez, the daughter of José Ignacio

Valdez and his wife María Manuela Sánchez from La Placita de los Dolores (now

known as Placitas). This Ignacio

is not to be confused with the other Ygnacio Valdes, and Chávez’ allegations

that Santiago married his adoptive foster-sister are incorrect. Chávez further

claims that Padre Martínez continued to hide Santiago’s patrimony when, on Oct.

29, 1849, he performed the marriage of Santiago Valdez to María Agustina Valdez

without entering the parents of either party, noting…”Bans dispensed with for

reasons contained in the Dilengencias Matrimoniales.”

[30]

It should be noted that the

baptismal records for the first three of Santiago and Agustina’s children have

Ygnacio Valdes as the adoptive paternal grandfather and María Estefana

Madril as the maternal grandmother.

Of the twelve children that

Santiago and Agustina had, seven survived and they were: Daniel, José David,

Teodora (Read), Malaquias, Marina (Romero), Mariquita (Montaner), and

Demóstenes,

[31]

and all

were given, and retained, the Martínez surname.

[32]

Demóstenes and his wife Ester Espinosa

would be my biological grandparents and Mariquita, and her husband José

Montaner, who adopted my mother were my adoptive grandparents. Interestingly,

my search in the Taos and Mora County baptismal records for the remainder of

the children born after 1856 has turned up cold after María Teodora´s birth in

1855. I suspect that their

baptisms may be in the records kept by Padre Martínez after his suspension in

1856.

Despite

his uncertain paternity, the will leaves no doubt about Santiago Valdez’

patrimony, and the degree that he was favored by Padre Martínez and where he is

recognized as a family member as follows: “I declare and dispose that in consideration to Santiago Valdez,

a member of my family, who I raised since infancy and adopted with all of the

privileges of a formal adoption, I educated, and that he recognizes no other

father, or mother, than me, and in addition to this he has been obedient to me,

for this I dispose, and it is my will that his children take, share, and carry

my surname in the future” (pp.6-7)

Santiago

Valdez was educated in the Padre’s school and went on to become a successful

attorney and politician. Based on Census records for 1860,

[33]

1870

[34]

and 1880

[35]

it is known

that Santiago and his family moved to Ocaté in the newly incorporated Mora

County sometime after 1860 but they were back in Taos by 1880. His political service included: Probate

Clerk, Taos County; Probate Judge and school board member, Mora County; State

Senator, Taos County (20 years); and a member of a commission that revised New

Mexico state Law in 1884. Santiago

served as the Captain of Company H 1st New Mexico Volunteers but

resigned his commission in late 1861, prior to the U S Civil War.

[36]

In 1877 Santiago Valdez authored the manuscript Biografía del Presbítero

Don Antonio José Martínez- Cura de Taos that

is housed at the Huntington Library near Los Angeles, and will be published by

UNM Press in 2008. He died on

April 13, 1888 however, a memorial card in my possession shows Santiago’s death

as April 19, 1888, and incorrectly gives his age as sixty.

[37]

Based on the baptismal record he would

have been sixty-eight.

The Romero Descendants

Little

is known about María Teodora Romero, but she was baptized as:

María Josefa Romero. Romero, Ma. Josefa -Vecina

[Taos] In this church of Taos on

the first of April, 1809, I solemnly baptized an infant girl born six days ago

and who was given the name María Josefa, legitimate daughter of José Romero and

María de la Luz Truxillo; the godparents are Ráfael Luna and Ana María Tafoya,

vecinos.

[38]

In Teodora Romero’s Last Will and

Testament of December 1888 she declared that she had been previously married to

José Oliver Vigil and that they had a daughter who was baptized and buried, and

that her husband had died in the same year as the child. She further states that in her state of

widowhood she had the below-named children whom she recognized as her

legitimate heirs.

[39]

The

first-born son was George Antonio baptized as follows: I, Don Antonio José Martínez,

the parish priest and pastor of San Geronimo de Taos, on May 1, 1831 baptized

in this parish a nine-day old infant [i.e., I supplied the ceremonies of

baptism, other than the pouring of the water]: I anointed him with Holy Oil [of Catechumens] and with

Sacred Chrism. Don Santiago

Martinez had already baptized him in emergency with water, saying in Spanish

the proper words of the required [Trinitarian] formula. The name of this infant is George

Antonio. He is a legitimate son of

Antonio Martinez and Maria Teodora Romero. His paternal grandparents are Don Antonio Severino Martinez

and Doña Maria del Carmel Santistevan, now deceased. His maternal grandparents are Don José Romero now deceased

and Maria de la Luz Trujillo. His

godparents were Don Santiago Martínez—the same one who poured the water

over him [George] —and Doña María de La Luz Lucero. All are vecinos of the neighborhood of

San Fernandes [de Taos]. I advised

them of their obligation [as godparents] and of their spiritual

relationship. So that it will

stand up [in law], I signed it

/span>Antonio

José Martínez

[40]

Don Santiago Martínez was the

Padre’s brother. It has been said

that the child was named in honor of George Washington. George married María Dolores

Medina and they had three children, Raquel, María de la Luz, and Bernardo. In 1882, fifteen years after the death

of Padre Martínez, the family sold their share of the Padre’s home to Santiago

Valdez, and apparently moved to the Ocate Valley in Mora County. Their granddaughter, Dora Ortiz

Vásquez, a daughter of María de la Luz, became the voice of the Romero progeny

of Padre Martínez when she wrote her book, Enchanted

Temples of Taos: My Story of Rosario. In her book Vásquez relates a series

of stories about life in the Padre’s household as told to her by María del

Rosario, the Navajo slave of Padre Martínez. In the book she refers to the relationship between Padre

Martínez and María Teodora as a marriage.

[41]

On

May 3, 1833, María Teodora Romero and Antonio Martínez had a daughter named

María de la Luz, who was baptized: In this parish of San Geronimo

de Taos, on May 9, 1833, I the Presbyter Don Antonio José Martínez, proper

pastor of the same, baptized [supplied the ceremonies for] an infant girl of

six days, and anointed her with Holy Oil and Chrism. Don Antonio Ortiz poured over her the water while saying the

appropriate words of the form, and giving her the name María de la Luz,

legitimate daughter of Antonio Martínez and of María Teodora Romero of San

Fernandes [de Taos]. Her paternal

grandparents are Don Severino Martinez and Maria del Carmen Santistevan. Her maternal grandparents are the

deceased José Romero and Maria de la Luz Trujillo. The godfather was the same servant baptizing [Antonio Ortiz]

and his godmother was his wife María Dolores Lucero, vecinos of the population

of Holy Trinity of Arroyo Seco. I

advised them of their obligation [as godparents] and spiritual relationship,

and so that this will stand [in law], I signed it

Antonio

José Martínez

[42]

It is presumed that she died

shortly thereafter because more than two years later María Teodora and Antonio

had another daughter who was also baptized María de la Luz: In this parish of San Geronimo

de Taos, on September 4, 1835, I the priest of Abiquiu, Don Francisco

Leyva, having come as a pastor,

solemnly baptized an infant girl born eleven days ago and anointed her with Holy

Oil and Chrism. I gave her the

name María de la Luz, a legitimate daughter of Antonio Martines and of María

Teodora Romero, vecinos of the Plasa of Our Lay of Guadalupe. Her paternal grandparents are Severino

Martines andMaria del Carmen Santistevan. Her maternal grandparents are José Romero and María de la Luz

Trujillo. The godparents were Juan

Manuel Lucero and Juana María Martines, vecinos of the Plaza of San Francisco

de Paula. I advised them of their

obligation [as godparents] and spiritual relationship, and so that it stand [in

law], I signed it

Francisco

Leyva

I give my testimony [that it

was signed before me] Antonio

José Martinez, Pastor.

[43]

In the Padre’s

will, he states that María de la Luz had been given a portion of the Padre’s

home as well as a house and land in Estiércoles

[44]

. Clearly, she was favored among the

daughters.

A third daughter, María Soledad was baptized: In this parish of Taos, on June

1, 1842, I the same pastor Antonio José Martínez, attended a celebration of

baptism that my associate priest Don José Vigil solemnly carried out. The name of this little girl of eight

days is María Soledad, natural [born out of wedlock] of María Teodora Romero, a

widow of the Plaza of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Her maternal grandparents are José Romero and María de la

Lus Trujillo. Her godparents were

José Antonio Otero and María Nicolasa Trujillo, vecinos of the same place. They were advised of their obligation

[as godparents] and spiritual relationship, so that it may stand [in law], I

have signed,

A.

José Martínez

[45]

In the will, no bequests are made

to María Soledad except to note that in describing his house, Padre Martínez

states that “It is a small square surrounded by porches on the inside, and the

wall on the north side belongs to the house of María Soledad, which I deeded to

her with a yard and back-corrals” (p. 2). Also, refer to Figure 1, Site 1 above for north extension to house.

On

April 5, 1844, Vicente Ferrer Romero was born to the widow María Teodora and

was baptized: In this parish of Taos, on April

20—I should have written it down yesterday—1844. I, the pastor,

Antonio José Martínez solemnly baptized a baby boy born on the 5th of this month, and I named him Vicente Ferrer, a natural son of María Teodora

Romero, widow and vecina of the Plaza of Our Lady of Gaudalupe. His maternal grandparents were José

Romero and María de la Lus Trujillo. His

godparents were Don Pascual Martinez and his wife Doña Ma. Teodora Gallegos,

vecinos of the Plaza of San Francisco de Paula. I advised them of their

obligation[as godparents] and of

their spiritual relationship, and so that it may stand [in law], I have signed

it,

Antonio

José Martínez

[46]

Like Santiago Valdez, Vicente

Romero was favored by Padre Martínez and was given a portion of the Estíercoles

land prior to the Padre’s death. In the will he is bequeathed goods from the estate valued at one hundred

and forty-one dollars, and with Santiago Valdez, is named as a Patrón of the “Chapel, its property and rights.” (p.6)

During his young life, Vicente witnessed the turmoil in

which Padre Martínez was embroiled. He was barely a teenager when the Padre’s letters decrying the

re-imposition of church tithes were printed in the Santa Fe Gazette, and about

14 when Padre Martínez was publicly excommunicated. These events most likely influenced Vicente to turn away

from the Catholic Church. Vicente seems to have had access to the Padre’s

printing press and used it to print religious tracts hostile to the Catholic

Church.

[47]

In 1872,

he and a former legislator by the name of José Domingo Mondragón approached

early Presbyterian missionaries and became founding members of the Taos

Presbyterian Church and Mission School, which they established on Vicente’s

land in El Prado (Estiércoles). Although they were licensed lay preachers, they were never ordained.

[48]

Vicente Ferrer served as an active and

effective lay-evangelizer for the Presbyterian Church at Laguna Pueblo and the

Taos/El Prado area. Vicente was married in the Presbyterian Church to Anastacia

Lucero of the family of Don Agustín Lucero. He died in 1924 at the age of 80. Most, if not all, of the Romero family members became

Presbyterians, as did Pascual Martínez, the Padre’s brother and nephew-in-law.

Pedro Sánchez may have flirted with the Presbyterian Church, but remained

Catholic.

And

finally, José Julio María de Jesús was baptized on December 25, 1850.

In this parish

of Taos, on December 25, 1850 I, the pastor, Antonio José Martínez solemnly

baptized a baby boy born six days ago, and I named him José Julio María de

Jesús, a natural son of María Teodora Romero, widow and vecina of the Plaza of

Our Lady of Gaudalupe. His

maternal grandparents were José Romero and María de la Lus Trujillo. His godparents were, Juan Ygnacio

Martines and María Casilda Matrines, vecinos of the Plaza of San Francisco de

Paula. I advised them of their obligation [as godparents] and of their

spiritual relationship, and so that it may stand [in law], I have signed it,

Antonio José Martínez.

[49]

Little is

know about Julio, but Padre Martínez, who acknowledged that he had not given

Julio anything during his lifetime, did, in the will, make a sizable bequest of

land, a portion of his house, and livestock with a total value of $800.

Rosario, the Navajo Captive

According

to Vásquez,

[50]

María del

Rosario was a Navajo Indian captive that Padre Martínez had purportedly

purchased for $150 dollars in about 1861.

[51]

Her Navajo name was Ated-Ba-Hozhoni, or

Happy Girl. Six years married and

with children - two boys and a girl--she and her daughter were captured in a

raid by “Spaniards” while the family

was encamped in a small canyon and taken to Taos. Placed into separate households by their captors, Padre

Martínez was able to reunite them into his household. He baptized and gave them Christian names, María del Rosario

and Soledad.

[52]

At one point during her tenure in the

Padre’s household, Rosario did manage to escape with two other Navajo slaves,

taking Soledad with them. María

del Rosario and her daughter were captured near the Rio Grande gorge, but the

other two managed to escape. According to Vásquez, Padre Martínez paid $150 for their safe return,

and after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, María del Rosario was

given her freedom, but she chose to remain with Padre Martínez. According to Rael-Gálvez, Padre

Martínez, in January 1861 and six months before his death, petitioned the Taos

County Probate Court not to free Rosario, his fámula (maid/servant), but to

make him her guardian,

[53]

and he baptized her in May 1867. In his will Padre Martínez

bequest a room in his house and 50 varas of farmland “amongst the fields of Martín Maes.” (p.6) He also asked that a room in his

house be “cut out” for her and that she remain at the election of the Romero’s.

[54]

After the Romero families sold their holdings Rosario, according to Vásquez,

went to the Ocaté Valley with them where she died at the age of 120.

[55]

Padre Martínez, in his testimony to the Dolittle Commission in 1865

described the captive/owner relationship as follows:

4th That there is an idea the the Indians

[held] captive and bought from their fathers, similar to the Yutas, who sell

their sons and daughters in exchange for horses and other objects are held as

slaves. No, they are servants and

are well treated; if they marry they are free to live in their master’s house

and pass their life as they please, the same as with the sons of Indians, who,

if not married when attaining their majority, become free after their marriage.

[56]

This

position has been one that has been long-held by Hispanos in northern New

Mexico when asked about the existence of slavery in nineteenth-century. There is a strong denial that

slavery existed in New Mexico as it did in the South, and the view now held is

similar to that as stated by Padre Martínez. The question of the use of

captives in nineteenth-century New Mexico has become a matter of debate among

New Mexicans, and although it has been historically defined as peonage, it is

still a form of slavery.

[57]

Also, according to Edmundo Vásquez, a

descendant of George Romero and son of Dora Ortiz Vásquez:

Padre Martinez's seeking guardianship for Rosario and

the Emancipation matter are not mutually exclusive. El Padre wanted to

protect Rosario for her years of service and companionship with the

family. As Dora told us, Rosario had no one to return to if she were to

return to the tribe, she had her daughter Soledad near as well.

Knowing that

prejudices against los indios was

rampant, Rosario's choice to stay with a family that wanted and loved her was a

benefit to the family, too. With the inheritance, she had economic

freedom - she had her own home in Ocate, married, had two sons and created her

own family. When the sons became adults they moved to Colorado and we

lost contact with them.

[58]

Final Notes

In the remainder of the will, Padre Martínez issued a

request asking that his executors include any property about which he may have

forgotten. His books, papers, and documents are left to Santiago Valdez for

preservation and safekeeping. In

the event that anything is left over from the estate he declares that it be

given, in equal parts, to his siblings Juana María, José María, Santiago, and

Pascual Martínez. Finally, in his

own testament about his life he declares that during his forty-two years of

spiritual administration that he fulfilled his ministry “with fidelity and good

faith” and that he did all he could to “enlighten the minds” of his fellow

citizens. He ends by stating that

in the event of any ill will towards him that “I never had the intention of

hurting anyone” (p.7).

The Two Burials

of Padre Martínez

Padre Martínez died on July 27,

1867. According to burial records

he was buried in his oratory, as requested in a ceremony officiated by his

student, friend, and fellow excommunicated priest, Mariano de Jesús Lucero on

July 29, 1867.

[59]

Twenty-four years later, on June 24,

1891, his remains were disinterred and taken in procession for reburial in the

Taos Association Cemetery located immediately northeast of Taos Plaza and now

known as Kit Carson Cemetery.

For many years, historians and

Padre Martínez scholars have wondered about how the remains of Padre Martínez

ended up at the Kit Carson Cemetery. The only clue available was provided by Dora Ortiz Vásquez in her now

out-of-print-book stating: “The

Padre’s body remained buried at the foot of the altar in his church [oratory]

for many years. When his church

was torn down, his body was taken out and again he had a solemn funeral, held

in his memory. This time his body

was buried at the Kit Carson Cemetery” (p. 78).

[60]

The cemetery was previously

known as the American Cemetery and the Taos Association Cemetery, and is

located on lands acquired by Padre Martínez from Don Ignacio Martínez and Felipe Sandoval in 1830. In 1837 Padre Martínez donated a

portion of this land to his housekeeper, María Teodora Romero, in payment for

services rendered. In 1847 he

provided another plot of this land for the burial of the seventeen Americanos

killed in the insurrection, hence the name American Cemetery. In a deed dated August 12, 1889, María

Teodora Romero sold for $20, a plot of land 45 feet by 32 feet to the Taos

Cemetery Association and acknowledged a previous gift of ten yards of land to

the Association.

In October 2006, Rev. Tom Steele,

S.J., of Albuquerque sent me a transcribed copy of an article that appeared in

the June 25, 1891 edition of El Monitor,

an early Taos newspaper, that described the reburial ceremony in detail. This ceremony took place twenty-four

years after his first burial in his oratory. His remains were disinterred and taken in procession for

reburial in the Taos Association Cemetery located immediately northeast of Taos

Plaza and now known as Kit Carson Cemetery.

This

second most solemn ceremony was described in detail in the June 25,1891 edition

of El Monitor as follows: At the

invitation of the Martínez family, the ceremonies began at the home of the late

Santiago Valdez, also described as the padre’s last residence and place of

burial. The ceremony began with

solemn Latin hymns sung by Inocencio Martínez, a nephew and student of Padre

Martínez, and then followed by a procession towards the cemetery. The casket was carried by the hermanos of the Society of San Antonio de Padua who sang an alabado as they marched. Officiating at the obviously Protestant dominated gravesite services

were Don Inocencio Valdéz, Jr., a member of the Valdéz family with whom

Santiago Valdéz was raised and Editor of El Monitor; Reverend Albert Jacobs, a Methodist minister serving Taos

and southern Colorado; and Reverend [José] Domingo Mondragon, a Presbyterian

Lay Minister; and Eulogio Montoya, a Taos Methodist Church Elder, both

converted contemporaries of Vicente Romero. Pedro Sánchez, a student and nephew-in-law of Padre Martínez

gave a heartfelt and eloquent eulogy.

[61]

Readings included Job, Chapter VII

[Job’s Life Seems Futile] and an excerpt from one of the sermons by T. DeWitt

Talmage, D.D.

[62]

that was

read in English by Don Inocencio Valdéz, Jr. and in Spanish by Don Guillermo

Martínez. Don Malaquias Martínez,

a son of Santiago Valdéz, spoke on behalf of the family expressing gratitude to

the participants. Of note, no

mention was made of the presence of the Padre’s son Vicente Romero or his

brother Pascual Bailon Martínez, both Presbyterians.

The

following inscription was engraved in Spanish on the tombstone:

In Memory of the Presbyter D. Antonio José Martínez

Priest of Taos N. Mexico

Born January 17, 1793

Died July 25, 1867

At the time of his death the New Mexico Legislature named

him

“The Honor of His Homeland”

He served his spiritual administration for forty-two years

The

Inventory, begun by Santiago Valdez on September 16, was concluded on October

10, 1867, with assistance of Evaluators Pablo Martínez and Diego Santistevan.

In the narrative of his Will, Padre Martínez gave complete descriptions of the

contents of the Chapel/Oratory and his land holdings, but the Inventory

contains only brief descriptions of each item listed. During the translation of these documents it was necessary

to cross-reference the items in the Inventory with the Will. The Chapel/Oratory contents are

consistent between the Will and Inventory, but as mentioned above, the

Inventory lists two oratories, within a single measurement, and two adjoining

cemeteries on a twelth of an acre or 5,533 square feet. Perhaps an architectural model can be

constructed to demonstrate the configuration. With regard to landholdings, the

Inventory is mostly consistent with the Will but it does not include the Arroyo

Seco and Arroyo Hondo properties. It is known that Don Antonio Severino Martínez owned similar holdings in

both communities, but not in Des Montes as listed in the Inventory. Don Severino was also an original

petitioner for the San Cristóbal Land Grant, and in his will this property was

given to his wife. Further research will be required to see how, when, and to

whom each property was transferred. The Inventory includes domestic animals not listed in the will such as

oxen and donkeys, and in addition to the cows under Partido, there were also goats.

The

will provides a brief description of home furnishings, but they are better

documented in the Inventory and include linens and mirrors from the bedroom and

kitchen utensils, consistent with the two rooms in which Padre Martínez may

have lived. The furniture described, such as the painted bookcase, a

fine dresser with mirror, mirrors with gilded frames, etc., are indicative of a

more contemporary and not Spanish Colonial, style.

[63]

Similarly, metal utensils and

objects such as crosses and wall sconces listed in the oratory may well have

been of American origin.

[64]

The textiles listed are consistent with

mid nineteenth century colors, designs, and styles of northern New Mexico. The jerga was a common textile found in homes then as well as today. Also listed among the firearms are

powder muskets, perhaps similar to those used in the Civil War. A scant few garden tools are listed,

but the blacksmith shop seems sufficiently equipped.

The inventory of books in the

library appears to be small for a man of letters and intellect, yet it does

contain subject matter close to the interests of Padre Martínez

–theology, philosophy, Latin, and canon and civil law. With his printing

press Padre Martínez used text from his books to publish textbooks for his

students. The late historian,

Antonio Gilberto Espinosa of Albuquerque, described one of the books as

follows: One of the most interesting volumes published by

Father Martinez was Derecho Civil (Civil Law), a small book bound

in cardboard covered with cotton print of a flowery pattern and sewed with

rawhide…On opening the book, the reader finds a title page, and eight

pages of a prayer manual, as if these pages were inserted after the book was

originally printed and bound as a reference book on law. Derecho

Civil is an excellent example of the avenues of thought and research, which

Father Martinez followed. It contains extracts from a wide variety of

fundamental works on law, which must have been in his possession… Derecho

Civil crams together, in a rather disorganized way, the rules of agency,

appellate, civil and criminal procedure, duties of attorneys and judges, the

rules of evidence, negotiable instruments, statutory construction end

testamentary law. There is included a form of Will, which, if properly

attested, would be admitted to probate today.

[65]

Also, this writer is aware of books that do not appear in the

Inventory that belonged to Padre Martínez. His signature on inside covers or

his handwriting of notes in the margins can identify such books. All of the books listed in the Will are

in public and private collections, such as a book on logic, Para, Francois,

1724-1797, “traducidos del latin al

castellano por el Señor presbitero D. Antonio José Martínez,” and two books

that are reprints published on the press of Padre Martinez: Instituciones

de derecho real de Castilla y de Indias, por él Dr. D. José María Alvarez, all held by the Beinecke

Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. Also that of Esriche held by UNM

Library.

[66]

Several of

these books have been displayed in museum exhibits.

The most impressive part of the inventory is the complete

listing of the contents of the Oratory, which are indicative of a man who never

left his ministry and remained a priest until death. Of the items listed, several of the vestments survive in

public and private collections, but only one painting La Purísima Concepción is known to exist. It is my hope that with the translation of this document, and with the

descriptions given, other items will surface.

Finally,

of note, the Inventory contains one error in addition in the amount of $82.00

that was not included in the sub-total of page 303 of the original document and

page 17 of the translation. The

last page was also missing the total value of the estate that came to

$9,556.20. Both of these errors

have been corrected and highlighted. Finally, further research needs to take place to locate the final

Probate of the will and the disposition of the estate, as well as documents

relative to the debts owed to the estate.

This

document contains much information that requires further scrutiny and our

readers are invited and encouraged to help with any insights, observations, or

errors that may be found in the transcription, translation, and interpretation

of the documents. Please send your

comments to: pml108@earthlink.net

ãFundación

Presbítero Don Antonio José Martinez 1/4/08

Part Three: The Inventory

[1] Ross Frank, From Settler to Citizen: New Mexican Economic Development and Creation of Vecino Society, 1750-1820, University of California Press, 2000.

[2] According to Padre Juan Romero, a Catholic priest and Padre Martínez scholar: In 1854 the Immaculate Conception 1854 the dogma was defined by Pope Pius XI who officially declared that Mary, from the first moment of her own conception within her mother’s womb, was preserved free from any taint of original sin… The liturgical celebration of Mary’s birthday is September 8, and the feast of La Immaculada Concepción is December 8.

[3] In his correspondence of January 28, 1856, Padre Martínez advised Bishop Lamy that he was in ill heath, suffering from a bladder infection and severe rheumatism in his legs, making walking difficult. He hinted at his possible resignation as pastor of Taos and asked that the Bishop consider Don Ramón Medina as his replacement and whom he would train, and upon completion thereof, he would resign. Archives, Archdiocese of Santa Fe [hereinafter: AASF]

[4] AASF Reel 30, pages 529-530

[5] Fr. Thomas Steele, S.J. (Personal Correspondence) January 22, 2007. [hereinafter: Steele]

[6] Pedro Sánchez, Memorias Sobre la Vida del Presbítero Don Antonio José Martínez, Santa Fe, 1903. [Herinafter: Sánchez, Memorias]

[7] Dora Ortiz Vásquez, Enchanted Temples of Taos: My Story of Rosario - Rydall Press, Santa Fe, NM, 1975. [hereinafter: Vásquez, Enchanted Temples of Taos]

[8] Steele, Transcription of El Monitor, June 25,1891; received October 2006.

[9] Steele, (personal correspondence) March 2007.

[10] David J. Weber, Edge of Empire: The Taos Hacienda of los Martinez, Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe, NM, 1996. Appendix, page 35. According to Ward Allen Minge in his translation of the Severino Martinez will: “Since the vara was equal to a pace they undoubtedly relied on measurements which had been paced off – yet measuring sticks were available.

[11] Identified in transcripts of legal instruments, Catalog umbers: 29, 33, and 35,

L. Pascual Martínez Collection, Millicent Rogers Museum Library, Taos. Alfredo Trujillo (personal phone call 10/07) identified the Coca land as being east of Taos Plaza towards, or near, Cañon in two, distinct sixty-three acre parcels, based on the descriptions in the transcripts.

[12] Instrument, Bargain, and Sale Deed, dated April 26, 1847 and Recorded 8/6/1874 in Book A-5, pages 83 to 85 in Records of Deeds in the Office of the County Clerk of Taos County, N.M. Attempts to locate the original copy of this deed in County and State records and archives have so far been unsuccessful.

[13]

Laura E.

Gómez, MANIFEST DESTINIES:The Making of the Mexican American Race, New York University Press, New York, NY, 2007, United States

vs. Lucero (Jan. 1869), pages 90-98.

[14] John Suazo, “Battle of 1847:Grandfather [Quan-na-na] Speaks: True Accounts of Pueblo Life,” The Horsefly:Taos Pueblo News Section, June 14, 2005; and Governor, Porfirio Mirabel, Testimony of Taos Pueblo, Indians of the United States: Investigation of the Field Service. Hearings: House Committee of Indian Affairs, House of Representatives, 66th Congress, 2nd Session, 1920.

[15] Identified in another part of the Will as José Miguel Martínez, Miguel Quintana, and possibly Manuel Miera. The will is not explicit as to the nature of their assistance.

[16] Vicente M. Martínez, BETRAYAL OR BENEVOLENCE: The Role of Padre Martínez and the 1847 Taos Trials and Executions, unpublished manuscript, 2005.

[17] Documento de Donación dated May 4, 1848, Recorded May 11, 1910, Book, A-20, page 278, Record of Deeds (NMSCRA). According to Santiago Valdez, Eulogio Valdez was a student and relative of Padre Martinez, and who began his studies in 1833 and was ordained in 1836.

[18] See: Alvar Ward Carlson, “New Mexico’s Sheep Industry, 1850-1900: Its Role in the History of the Territory,” New Mexico Historical Review, XLIV: 1 (1969); and Charles Montgomery, The Spanish Redemption: Heritage, Power and Loss on New Mexico’s Upper Rio Grande, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA, 2002, pages 35-36.

[19] Steele: Report by Bishop Talbot to his superior, Bishop J. Dixon Carder, May 21, 1863.

[20] Identified as housekeeper in my family oral history; as Madre Teodorita and “wife” of Padre Martínez by Vásquez, Enchanted Temples of Taos; and as a “neighbor” by Chávez, But Time and Chance. Chávez also cites the 1850 Territorial Census that lists Teodora as living next door to Padre Martínez, pages 38-39.

[21] New Mexico Genealogist “The Progeny of Padre Martínez,” 46:55-65 (2007) and “Postscript to the Progeny of Padre Martínez,” 46:181-188 (2007).

[22] I am grateful to Nancy Anderson, President of the New Mexico Genealogy Society who scanned AASF microfilm and sent me actual baptismal records, and Alberto Vidaurre, a genealogist from Taos who searched local archives to help clarify the records.

[23]

Last Will

and Testament, [hereinafter Will] page 2. Also, Martínez and Valdez differ on the daughter’s year of death.

[24] Manuel Martínez and his family were recipients of the Tierra Amarilla Grant. José Vicente, a brother of María de la Luz, was my paternal great-great grandfather.

[25] Chávez, But Time and Chance. Chávez incorrectly identifies him as José Santiago Marquez baptized on February 10, 1830, illegitimate son of María Teodora Márquez and that with regard to the natural father, a note would be found in a confidential notebook, page 33.

[26] The surname, Madril, was changed to Madrid in the baptismal records of the Valdez children.

[27] AASF Book 47, Taos, Frame 897

[28] Email correspondence from John Peña, July 16, 2007. “First, my maternal grandfather, Ignacio Luján, always claimed that his maternal grandfather, Ygnacio Valdés, had reared Santiago for Padre Martínez, who were political allies.”

[29] Ibid. Chavez, But Time and Chance, page 38.

[30] Ibid., Chavez, But Time and Chance, page 34. Also see AASF B-47

[31] Ruth Fish, “Illustrious Early Taos Mother,” The Taos Review, February 15, 1940.

[32] Of the four baptisms that I reviewed, the children were baptized with the surname Valdez. The surname Martínez was most likely taken after the Padre’s death.

[33] U.S. Census 1860, Taos, Taos County, NM; National Archives microfilm, Series M653, roll 715, page 300.

[34] U.S. Census 1870, Ocate, Mora County, NM; National Archives microfilm, Series M593, roll 894, page 363.

[35] U.S. Census 1880, Taos, Taos County, NM; National Archives microfilm, Series T9, roll 804, page 209.

[36] Interview with Jerry Padilla, Taos, NM September 2006.

[37] Someone used a pencil to cross out the age “60,” and wrote what appears to be a 6 and an 8. The first penciled number is not completely legible, but the 8 is clear.

[38] AASF #19, Frame 84, Entry # 10. Padre Martínez made a later notation to the baptismal record giving her name as María Teodora. Also, Vásquez: Enchanted Temples of Taos, provides a genealogical sketch that shows María Teodora as Teodorita Santistevan y Romero. page x.

[39] Last Will and Testament of Teodora Romero, 1888 in Abstract of Title.

[40] AASF # 20 Frame 83

[41] Ibid. Vásquez: Enchanted Temples of Taos. "He believed priests should marry. He was married to Madre Teodorita and his family was legitimate. He had been married before he was a priest, and his first wife died; he had a daughter from her who also died," page 50.

[42] AASF # 20 Frame 378

[43] AASF # 20 Frame 639

[44] NMSCRA, Dote de María de la Luz Romero, Deed & Mortgage Record A-1, 1853-1869, Taos Co., pages 19-21.

[45] AASF # 21 Frame 408

[46] AASF # 21 Frame 598

[47] Padre Juan Romero (Personal Correspondence)1/16/06.

[48] Tomás Atencio, "The Empty Cross: The First Hispano Presbyterians in Northern New Mexico and Southern Colorado", in Protestants/Protestants: Hispanic Christianity within Mainline Traditions, David Maldonado, ed.(Nashville: Abington Press,1999); pages 38-59. Also, the purported ruins of the mission church are located just north of Overland Sheepskin Co. in El Prado.

[49] Archdiocese of Santa Fe, Taos Baptisms, 1850. LDS Microfilm 001710.

[50] Parts of this narrative are adapted from Vásquez, Enchanted Temples of Taos.

[51]

Estevan

Rael-Gálvez, “Rosario’s Secret: A Story of Slavery and Loss of Identity,” New

Mexico Magazine, March 2007, page 62. [hereinafter, Gálvez-Rael, Rosarios

Secret]

[52] According to Gálvez-Rael no record of the baptisms exists, Rosarios Secret, page 62.

[53] Ibid., Gálvez-Rael, Rosarios Secret, Illustration, page 62: “Dario de la Corte de Pruebas, Termina en 1867, Taos County Records,” Probate Proceedings, C-3, ca. 1860-1867. Caption, “at a time when Rosario should have been emancipated as a slave, Padre Martínez sought to be her legal guardian in probate court which, determines claims on possessions.”

[54] Gálvez-Rael, Rosarios Secret. Gálvez-Rael does not mention her alleged emancipation or bequest in the Padre’s Will.

[55] Ibid., Vásquez, page 78.

[56]

Steele:

Transcript of Padre Martínez’ testimony given to me in May 2007. U.S., Congress, Senate, Condition of

the Indian Tribes: Report of the Joint Special Committee Appointed under Joint

Resolution of March 3, 1865, S. Rpt. 156,

39 Cong. 2 sess., 1867, (Dolittle Report).

[57] The issue of slavery and captives will be addressed in two forthcoming studies on the subject by New Mexican scholars: Laura E. Gómez, MANIFEST DESTINIES:The Making of the Mexican American Race, New York University Press, New York, NY, 2007; and Estevan Rael-Gálvez, New Mexico State Historian, “Identifying Captivity and Capturing Identity: Narratives of American Indian Slavery, Colorado and New Mexico, 1776-1934,” unpublished Ph.D. manuscript slated for publication in the near future.

[58] Email correspondence from Edmundo Vásquez, 2/9/07.

[59]

AASF, Our Lady of Guadalupe Book of Burials,

42a. “Yo el presbítero Mariano de Jesús Lucero, en su

Oratorio privado del cura Antonio José Martínez en la plaza de Nuestra Señora

de Guadalupe, dí sepulcro al cadaver del mismo Presbítero Don Antonio José

Martínez habiendole administrando antes los Sacramentos de penitencia, anto

Viático y Estre Unción; y para la debida constancia firmé. SS: Mariano de Jesús

Lucero”

[60] Ibid. Vásquez, p. 78

[61] In Sánchez, Memorias, a brief eulogy appears at the end of the final chapter.

[62] El Monitor, July 1891, printed the full text in Spanish: “Death, the Gateway to Joy (La Muerte, Entrada al Gozo).” Thomas DeWitt Talmage (1832-1902) was an American Presbyterian preacher, writer and lecturer. Source Wikipedia.

[63] Observation made by Ward Allen Minge in a letter dated 1/17/06. “I found it interesting to compare the Padre’s will and Severino’s…It [Severino’s] lists the greatest variety of colonial materials I’ve been able to find in earlier wills. The Padre’s will by contrast, reflects influences from Santa Fe Trail traders.”

[64] Steele, (Personal correspondence) March 2007. “Tinwork began in Santa Fe about 1830 when the Santa Fe Trail brought tin goods, lead and cheap paper engravings, woodcuts, lithographs from Currier & Ives and European images, largely religious.”

[65] Antonio Gilberto Espinosa (d. 1967), The Curate of Taos: A Story of the Formative years of Modern New Mexico History. (Based upon the life and times of Antonio José Martínez y Santistevan 1793-1867), Unpublished manuscript, 1967, page 30. Printed with permission from Maggie Espinosa McDonald, owner of manuscript.

[66] Escriche, Joaquin, Diccionario razonado de legislación civil, penal, comercial y forense; ó sea Resumen de la leyes, usos prácticos y costumbres, como asimismo de las doctrinas de los jurisconsultos, dispuesto por orden alfabético de materias, con la esplicación de los términos del derecho. París, M. Alcober Banquero, 1831.

Escriche’s famous dictionary appeared in many editions. 1831 might be the first edition—but there were several afterwards. Email from David Weber, 5/8/06.

Intro and comments

| English |

| Spanish |

|

Welcome |

About Us |

About Padre Martinez |

Virtual Library |

Virtual Museum |

El Crepusculo de la Libertad |

Links |